Borrowing from science fiction, the manual Beyond Smart Cities (available at my Amazon store) envisions a city, a smart city, which took the leap into the realm of autonomy. That is, the book has drawn from the concepts of the sustainable-city technology to establish a city which is independent of its environment and public utilities. The manual provides detailed instructions on creating an autonomous, or 'sealed', city, an ideal model which supplies its own energy, food, and fresh water to its inhabitants. The purpose of such a structure, as stated, is to provide an energy-efficient dwelling in areas subjected to adverse environmental conditions and to accommodate exponential growth.

Here, we discuss the current status of smart cities and their support systems, while demonstrating our notions of the next logical and security-oriented step for inclusive technologies which are superimposed throughout the text. Of course, initiating this architectural approach will require multidimensional approaches across sectors. Among them, improving sustainability of sealed-city urban development is critical because normal urban cities, home to 67% of the world’s population by 2050 (UNDESA, 2012), serve as a double-edged sword in the context of sustainable development.

**A sealed city is essentially a large housing structure containing residential dwellings, commercial establishments, farms, water-treatment facilities, and recreational venues under a common roofing system. The model used in the manual has an area of one square mile, or 259 hectares.**

On one hand, cities functions as the main engine of economic growth. Overall, 60% of global GDP can be attributed to 600 cities around the world . In OECD countries, only 2% of their regions, mostly the largest urban areas, generate roughly one-third of all growth (OECD, 2011). In India and China, the five largest cities’ economies are responsible for approximately 15% of national GDP (UN Habitat, 2010). In general, there is complex but positive correlation between urbanization and economic growth. Urbanization is often characterized by agglomeration of production, which leads to increased productivity and greater investment interest. Providing more employment opportunities and higher salaries brought by competitive labor market and elevated productivity further helps stimulate economies as a whole. A recent study by Credit Suisse found that every 5% point increase in urban population pushes up per capita economic activity by 10% (Credit Suisse, 2012). On the other hand, cities face a number of social and environmental challenges, growing in tandem with the today’s unprecedented pace of urbanization.

Globally, more than one billion people live in slums (World Bank, 2013), with limited access to basic social services, economic activities and, without security of tenure, many of them live under constant threat of eviction. Cities also contribute to global environmental pressures. They account for an estimated 67% of global energy use, and up to 70% of global green gas emissions (IEA, 2008 and 2010), mainly due to the concentration of industrial production, transportation and construction. There are also mounting problems of waste management control and water and air pollution, posing increasing threats to inhabitants’ health and well-being. In more than 65% of the cities in developing countries, water is not properly treated. Between 30 to 50% of the solid waste generated within most cities is not collected (UN-HABITAT, 2009). All these challenges are further exacerbated by rapid and unplanned urban expansion that tends to increase resource inefficiencies (e.g. energy and land use) and costs for social service delivery. Urban areas are also increasingly susceptible to natural disasters, mostly because of their common location along waterways, as well as population and infrastructure densities. As a UNISDR report suggests, the rate of natural disasters in urban areas has increased four-fold since 1975 (UNSDR, 2011), and in many disasters, the poor and vulnerable are disproportionately affected.

Furthermore, according to the 2011 UN Report on Urbanization, of the more than 1.4 billion people in the world residing in urban areas of at least 1 million inhabitants, 60 per cent, or roughly 890 million people, were living in areas of high risk of exposure to at least one natural hazard (UNDESA, 2011).

**Use of RFID (Radio-frequency identification) systems in a sealed city. These systems allow only those registered to enter the parking structure. As recommended by the manual, only electric vehicles are allowed on the streets of a sealed city.**

Despite these challenges, well managed sealed-city development could give rise to cities more conducive to economic growth and social inclusion, environmentally sustainable and resilient to climate change, natural disasters and other risks. The Sustainable Development Solutions Network’s Thematic Group on Sustainable Cities, established to facilitate the discussion on the Post-2015 under the UN framework, illustrates the numerous opportunities available to cities if sustainable urban development is realized. Given the concentration of economic activities in urban areas and significant investment opportunities, particularly in emerging and developing economies, there is ample opportunity and motivation to reengineer cities in a more sustainable manner. By all accounts, well-managed cities will use natural resources and technology more effectively, which will have a positive and substantial impact on society, the economy and the environment.

What is required to achieve sustainable urban development varies from country to country, but comprehensive interventions from up-stream policy and standard setting to down-stream project design and implementation are vital. Responding to these challenges, the international community has made headway on a variety of fronts. Defining sustainable urban development and setting standards is the first step towards widely diffusing the concept. Standard-setting is also instrumental in creating new markets. A number of international organizations and donors are advancing their work in these areas through research and dialogue. There is also a large funding gap in the urban development sector. Global demand for infrastructure development is enormous, exceeding some US$ 5 trillion annually under current growth projections. Furthermore, an additional US$ 700 billion is required to support the ambitious goals of the IEA to limit average global temperature increases to 2°C above pre-industrial levels (WEF, 2013). This large funding gap cannot be met by public spending alone. Unfortunately, securing long-term private finance for infrastructure investment is becoming increasingly difficult due to recent economic downturns.

**Fresh-water supply is an essential component of a sealed city, especially when located in arrid climates.**

Measures have been taken by various governments to leverage private finance, but scale and pace need to be upgraded significantly. Public-sector support in green investments, if increased up to US$ 130 billion and targeted more effectively, could mobilize private capital in the range of US$ 570 billion, which would near the US$ 700 billion of incremental annual investment required to facilitate greener growth. However, greening the remaining US$ 5 trillion investment requirement in the business-as-usual growth projects will continue to present a major challenge; comprehensive policy reform and a stronger push toward investment-grade policy initiatives will be required to fully address demand (WEF, 2013).

**Housing will be available according to the customer's needs in a complete sealed city. Housing units should range from single family homes to studio apartments to penthouses.**

Defining sustainable urban development and setting standards

The concept of the sustainable city first emerged and evolved as Western countries were striving to tackle increasing urban sprawl and environmental issues in the 1970s. The concept, now known as Sustainable Urban Development (SUD), has gained even greater prevalence in recent years, as the world has begun to place increasing emphasis on the importance of controlling the effects of rapid urbanization and climate change. SUD is commonly understood as an approach that stresses ―sustainability as its main feature, embracing social and economic structures that do not compromise environmental aspects (UN-HABITAT, 2002). SUD is underpinned by mechanisms aimed at producing co-benefits like (i) inclusive economic growth, (ii) competitive economies, (iii) social fairness and equality, (iv) safe, secure and comfortable environments, and (v) environmental friendliness, including conservation of local and global public goods.

The concept of the sustainable city first emerged and evolved as Western countries were striving to tackle increasing urban sprawl and environmental issues in the 1970s. The concept, now known as Sustainable Urban Development (SUD), has gained even greater prevalence in recent years, as the world has begun to place increasing emphasis on the importance of controlling the effects of rapid urbanization and climate change. SUD is commonly understood as an approach that stresses ―sustainability as its main feature, embracing social and economic structures that do not compromise environmental aspects (UN-HABITAT, 2002). SUD is underpinned by mechanisms aimed at producing co-benefits like (i) inclusive economic growth, (ii) competitive economies, (iii) social fairness and equality, (iv) safe, secure and comfortable environments, and (v) environmental friendliness, including conservation of local and global public goods.

A recent study identified more than 200 varieties of SUD definitions across the globe. It will be important to establish a clear definition and common standards for SUD if the concept is to be integrated into the mainstream. Efforts are already underway to address this issue, but more work remains to be done.

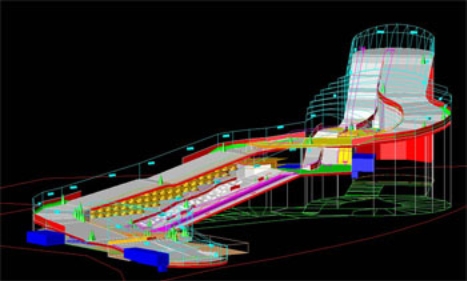

**Indoor amusement parks and ski lodges, open year-round, are examples of sealed-city venues available to non-citizens and represents a steady income stream.**

Global public efforts to define the SUD concept

The concept of SUD has been promoted at the international level through a multitude of forums and conferences, as a part of a global endeavor to help cities cope with emerging development challenges. The Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlements and the Habitat Agenda, adopted at the Second UN Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II) in Istanbul in 1996, emphasized that urban development should give ―full consideration to the needs and necessities of achieving economic growth, social development and environmental protection (The Habitat Agenda, 1996). UN-HABITAT has since accelerated its work in monitoring urban conditions worldwide and created the Global Urban Indicators Database, which contains indicators covering 5 functions of cities: shelter, social development and eradication of poverty, environmental management, economic development and governance. It now serves as a global framework for cities to define and monitor their urban issues. More recently, SUD has also been discussed for the Post-Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Post 2015 Development Agenda. In fact, "make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient" was incorporated as Goal 11 of the final proposal by The UN Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals in 2014. In tandem with the official negotiation process, numerous proposals for SUD goals and indicators have been put forward.

A majority of these proposals consider SUD as a dynamic process and have emphasized the importance of integrating economic, social and environmental objectives and encouraging measures to mainstream comprehensive planning and management. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has also contributed to constructing and promoting international SUD standards. Building on member countries’ abundant experience and knowledge, the OECD has created systems for reviewing city development policies and produced policy papers for public use (OECD, 2012). More recently, it established a Green Cities Programme, which developed a set of indicators and policy recommendations on cities’ environmental performance. The Programme provides insights into the types of green urban policies that are most likely to facilitate certain desired economic results, for example, to incentivize cities to promote SUD. The Programme is now being extended to cities in developing countries to assist them in establishing their urban green growth strategies and relevant indicators. International organizations have also collaborated with local governments to help establish standards for SUD. One example is the Global City Indicators Facility (GCIF) which was originally created by the World Bank and is now managed by the Canadian Government. The Facility is characterized by its focus on the soft component of SUD, featuring city services and quality of life factors. Establishing this set of indicators under a globally standardized methodology allows for global comparability of city performance -a positive step towards laying a foundation for SUD standards and a useful tool for knowledge-sharing.

**Models for a livestock/greenhouse complex (top); Plan for a police station (bottom).**

Work in the SUD field is also progressing at the regional, national and sub-national levels. The situation is diverse, reflecting complex and distinct histories, political systems and stages of development. One example of evolution at the national level is Malaysia’s Low Carbon Cities Framework, which underpins the government’s target to reduce carbon emissions by 40% by the year 2020. The framework intends to mainstream the concept of low carbon cities, and help local authorities make decisions and design action plans for greener urbanization. The framework employs a monitoring mechanism which contains clear performance criteria and indicators based on the priority aspects of urban development for GHG reduction: (i) urban environment, (ii) urban transportation, (iii) urban infrastructure, and (iv) buildings. Japan´s Comprehensive Assessment System for Built Environment Efficiency (CASBEE) is another interesting example. The system was developed to serve as a tool to assess and evaluate the environmental performance of buildings. The tool has now evolved to contain frameworks to help cities pursue their SUD policies; CASBEE-For Urban Development helps evaluate the environmental performance of areas beyond one specific building, and CASBEE-For Cities provides a framework to evaluate environmental performance with full consideration of both social and economic factors. The system is used by a number of Japanese local authorities and is being rolled out into the entire Asian region.

**Simplified control infrastructure of a sealed city.**

The private sector

The private sector has also acknowledged the importance of standard setting for market development. Some international corporations are trying to develop their own indicators to define and monitor cities’ SUD performance in order to expand and strengthen markets for SUD-related businesses. On example is the International Standards Organization (ISO), which has created Environmental Management Systems (EMS) – voluntary measurement instruments that can be utilized by public and private sector managers to improve environmental performance. The system provides a set of policies and procedures for the supervision, control, reduction and prevention of activities that impact the environment. These kind of tools help communities formulate and implement holistic, cross-sector and area-based approaches to development, and set a solid foundation for progress and sustainability. The ISO is also leading a discussion to establish international standards on sustainable city development through its Technical Committee on Sustainable Development in Communities (ISO/TC 268) and subsidiary bodies which discuss city indicators (ISO/TC 268 WG2) and smart community infrastructures (ISO/TC 268 SC1). The Committee is currently examining requirements, guidance, and supporting techniques and tools to help cities and other stakeholders realize SUD. Notably, unlike conventional ISO standards that intend to promote product standardizations, the ISO/TC 268’s work defines the actual business fields by specifying and standardizing infrastructure related services. This essentially provides an international guarantee to the scope of the business, thereby contributing to market creation. This is indeed a welcoming trend, with the potential to advance SUD through a more market-based approach.

The Future of Smart Cities and Smart Sealed Cities

The world is in the midst of a sweeping population shift from the countryside to the city. Urban dwellers will likely account for some 86 per cent of the population in more developed regions and for 64 per cent of that in less developed regions (UNDESA 2012). This transition presents many challenges including slum build-up, income inequality, increased consumption and solid-waste, intensified use of natural resources and greenhouse gas emissions, among others. And these challenges are exacerbated by unplanned city expansion and urban sprawl. Consequently, the choices that city planners make to manage the process of rapid and increasing urbanization will have profound consequences for citizens´ well-being and economic future. Urban professionals must collaborate with architects, engineers, landscapers, transportation coordinators and land lawyers, as well as environmentalists and community members to ensure a holistic and inclusive approach to city design and management in the Post-2015 era. Cities in developing countries face a wide range of administrative, technical, and financial limitations that make it difficult to deal with the challenges of rapid and increasing urbanization. Inefficient institutional structures and disjointed budgets, timelines and goals have often led to fragmented urban planning solutions. With limited access to finance, governments in many developing governments must look to improve their investment environments through macroeconomic policy and regulatory reform and by securing project cash flows. Better service delivery and infrastructure management will help increase public support for user fees and tax collection mechanisms.

**Alternative roofing structures for a sealed city.**

There is an urgent need to capture more private sector resources; funding SUD is beyond the means of public expenditure. More innovative financial products will be required, as well as greater support from development banks that can mobilize a wide range of domestic and international resources, provide the leverage to tap new markets and private investors, not only providing country risk guarantees to help ensure lower interest rates, longer maturities and more flexible debt parameters, but also helping structure pooled initiatives that reduce individual investment costs. Development banks can also help improve investment climates by guiding PPP policy and institutional framework reform, backing PPP pilot projects and structuring financing vehicles that help provide attractive risk/return profiles for private investors. In addition to their financing support, development banks can offer technical assistance for policy, institutional and capacity development and promote knowledge sharing programs and networks, data collection and feasibility studies that can help governments design and apply comprehensive and effective urban growth strategies. The importance of Sustainable Urban Development has gained substantial momentum in recent years; measures to mainstream comprehensive planning and management, incorporating economic, social and environmental factors are now widely promoted in the international development community. Standard setting will continue to be instrumental in diffusing the concept, as well as creating new markets for integrated interventions that attract private sector actors. Although many useful city planning tools are available, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to accommodate the diverse set of challenges and threats cities face. However, the following have been identified as key factors in SUD strategy and policy formulation: ·ensure comprehensiveness and incorporate more proactive and incentivizing measures for local authorities to tackle high priority issues (e.g., poverty reduction or climate change)

·promote stakeholder coordination and participation to ensure the integrity of urban development,

·identify inter-linkages among different and sometimes conflicting needs, maximize synergies between them where possible, mitigate unintended consequences of a policy and address problems in a sequenced manner,

·encourage "co-benefit" measures that can cater to multiple needs through a single policy intervention and utilize fewer resources,

·effective regulatory and financial frameworks to enhance implementation, and

·built-in mechanisms to monitor and revise strategies to accommodate changing needs

Sealed-city urbanization is advantageous in many ways. With growth comes the benefits from agglomeration or economies of scale that improve productivity in many local industry and service sectors. In fact, delivering basic services such as water, housing and education will be less costly in concentrated population centers than in sparsely populated areas, which is a significant advantage in highly arrid or wintry regions.

Autonomous 'sealed' cities will also attract the most talent and inward investment, and will likely be at the center of a cluster of smaller cities, which creates network effects that spur even greater economic growth and productivity. However, leaders must be able to respond to the increasing complexity of all cities, and provide effective planning and management capable of both mitigating the risks and exploiting benefits of urban growth. Any SUD sealed-city strategy should give rise to cities more conducive to economic growth and social inclusion, environmentally sustainable, and resilient to climate change, natural disasters and other risks. ◼